Chapter One - Nord and Sud Express

Introduction

Paul Selver translated the book at the time, and it reflects a dated language compared to what we use today. But that makes the book more entertaining.

The book is made even more special by the hand drawn illustrations which mark many pages, with the image linking to the text.

Chapter One - Nord and Sud Express

Time after time in modern poetry the Transcontinental Express dashes past you, and a mysterious porter calls out the names of stations: Paris, Moscow, Honolulu, Cairo; the Sleeping Cars dynamically scan the rhythm of Speed, and the Pullman, as it whirls by, suggests all the magic of distant places, for you must know that nothing less than first-class travel accommodation will satisfy the fine frenzy of the poet.

My poetical friends, allow me to tell you the plain truth about Pullmans and Sleeping Cars: if you must know, they look infinitely more enticing from outside, when they flash past some sleepy little station, than for within. It is true that they make up for this by their tremendous speed, but it is no less true that at the same time you are boxed up in them for fourteen or even twenty-three blessed hours at a stretch, and as a rule that's enough to bore you stiff.

A local train from Prague to Repy jogs along at a less impressive speed, but at least you know that in half an hour you'll be able to get out and pursue some new adventure.

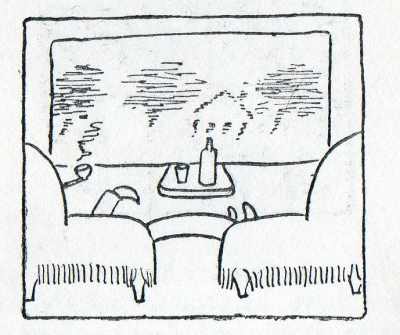

A man in a Pullman car doesn't dash along at sixty miles an hour; he just sits and yawns; if the face on the right annoys him, he goes and sits down on the other side. The only redeeming feature of it is that he has a comfortable seat. Sometimes he gazes listlessly out of the window; a small station whisks past, and he can't read the name of it; a township flits by and he can't get out there; he'll never stroll along that road boarded with plane-trees, he'll never dawdle on that bridge and spit in the river - in fact he won't even find out what the river is called. Confound it all, thinks the man in the Pullman, where are we? What only Bordeaux? Good Lord, this is a slow business.

Wherefore if you want to have a trip with at least something exotic about it, get into a local train which puffs its way along from one wayside station to another. Press your nose against the window-pane, so as not to miss anything: here a soldier in a blue uniform gets in, here a child waves its hand at you; a French peasant in a black cowl lets you have a swill at his wine, a young mother gives her baby a breast as pale as moonlight, the country yokels hold forth noisily and smoke their shag, a snuff-stained priest says his breviary; the land unwinds, station after station, like the beads on a rosary.

And then evening comes, when the jaded passengers doze like emigrants under the flickering lights. At that moment the lustrous International Express hurtles past on the other track with its load of weary boredom, with its Sleeping Cars and Dining Cars.

What's that, only Dax? Heavens above, what a tiresome journey!

Not long ago I read a eulogy of the Suit-case; of course, not the common or garden suit-case, but the International Suit-case, plastered over with hotel labels from Constantinople and Lisbon, Tetuan and Riga, St. Moritz and Sofia; the suit-case which is the pride of its owner, whose travels it records. I will reveal a dreadful secret to you: those labels are sold in travel agencies. For a moderate fee your suit-case will be labelled Cairo, Flushing, Bucharest, Palermo, Athens and Ostend. With this revelation, I hope, I have inflicted a mortal wound in the International Suit-case.

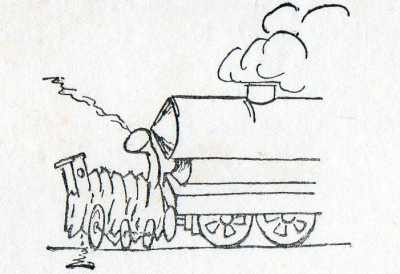

It is possible that another man in my place, travelling all those thousands of miles, would meet with something different in the way of adventures; perhaps he could come across the International Venus or the Madonna of the Sleeping Cars. Nothing of that sort happened to me; there was only a collision, but I really couldn't help that. In some wayside station our express dashed into a goods train; the contest was an unequal one and the result of it was much the same as if Mr. Chesterton had sat on somebody's top-hat.

The goods train fared very badly, while on our side there were only five wounded; it was a thorough victory. When, in such a contingency, a passenger has wriggled out from under a suit-case which has fallen on his head, he first of all rushes to see what has happened; and not until he has satisfied his curiosity does he begin to fumble about to discover whether he has any broken bones. When he has made sure of that, roughly speaking, he is sound in wind and limb, he derives a certain amount of technical pleasure in observing how the two engines have got rammed together and what a thorough mess we have made of the goods train; well, it oughtn't to have interfered with us.

Only the injured passengers are pale and rather disgruntled, as if a personal and unjust humiliation has been inflicted upon them. Then the authorities poke their noses into it and we go off to drink to our victory in the remnants of the dining-car. For the rest of the journey they leave us a free passage, we have evidently put the fear of God into them.

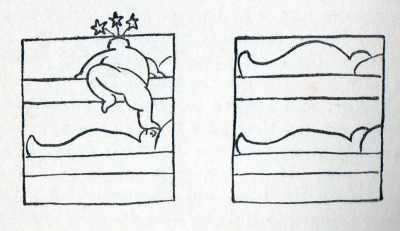

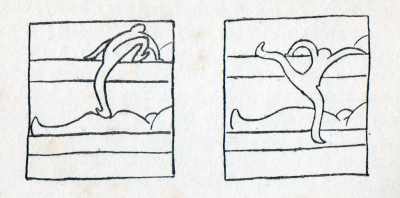

Another and more complicated adventure is how to get into the upper berth in a sleeping-car, especially when someone is already asleep in the lower one. It is somewhat disconcerting to trample on the head and abdomen of a person whose nationality and character are alike unknown to you. There are various wearisome methods of getting on top; by such physical jerks as the upward stretch, with or without a preliminary jump, by vaulting, by straddling, by fair means or foul.

Once you are up there, make sure not to get thirsty or anything of the sort which would involved climbing down; surrender yourself to the hands of God, and try to sleep like a corpse in a coffin, while unknown and strange regions past outside, and at home poets are writing verses about International Expresses.