Chapter Fifteen – Alcazar

Alcazar

FROM the outside it is a mediaeval, notched wall of are ashlars; but within, it is a Moorish castle covered with verses from the Koran and bedecked from top to bottom with all the weird hocus-pocus and sorcery of the Orient.

You must know that this Arabian Nights castle was built by Moorish architects for a Christian King. It was in the year of grace 1248 (as they say in historical novels) when Christian king Ferdinand entered the captured Moorish City of Seville on St. Clement’s Day; but he was assisted in performing this Christian deed by one Ibn al Ahmar, Sultan of Granada, from which it is obvious that religion has always been hand in hand with politics.

Whereupon the Christian king, for reasons which were doubtless pious and enlightened, drove three hundred thousand accursed Musulmans out of Seville; but three hundred years later the Moorish masters where building palaces for the Christian kings and hidalgos, and were covering their walls with subtle ornamentation and Cufic surahs from the Koran. Which fact throws a peculiar twilight on the age-long struggle between Christians and Moors.

And if I had to describe the patios, the halls and the apartments of the Alcazar, I would set about the task like a builder; I would first of all collect the material, she as stone and majolica, stucco, marble and precious timbers, and whole cartloads of the loveliest words for mixing the mortar of my prose style; then, as builders do, I would start from the bottom, from the faience floors; on top of that I would place the slender marble pillars, keeping a sharp eye on their sockets and capitals, but I would pay particular care to the walls inlaid with the choicest majolica tiles, overspread with lacework of stucco, emblazoned with a whole delicate and lustrous colour-scheme, pierced by windows, arcades, apertures, trellises,ajimez, and galleries in accordance with the noble order of the horse-shoe, the broken arch, the circle and the lobe; whereupon, above all this I would arch aloft the vaultings and ceilings of stalactites, meshes and networks of stucco, star-patterns, coffers, faiences, gold, paintings and carvings, and having done all this. I should feel thoroughly ashamed of my bungling efforts; for it cannot be described like that.

A better way would be for you to take a kaleidoscope and turn it round and round until the sight of that endless geometry makes you feel dizzy; watch the rippling of water until your senses are benumbed; drug yourself with hashish until you see the whole world turning into an endless series of dissolving patterns; add to this everything that intoxicates and beguiles, that is opalescent and voluptuous; everything that clouds the senses; everything that resembles lace and brocade, filigree and jewels, the treasure of Ali Baba, precious fabrics, a stalactite dome and the mere stuff of dream; and through this many-tinted, fantastic and almost crazy array you must suddenly pass a comb so as to produce a tremendously neat, dainty yet strict arrangement, a quiet and contemplative constraint, a sort of dreamy and wise renunciation, which deploys these fairy-tale treasures in an almost immaterial and unreal surface, soaring upon fragile arcades.

This unutterable pomp is so dematerialized in its surface that it becomes almost a mere vision projected on to the walls. How material, gross and ungainly is our art, appealing almost more to the sense of touch than of sight, when compared with the work of these strange Moors, we just clutch and handle things which please us; we pass our hands over it roughly and brutally, with a gesture of ownership.

Heaven alone knows what sense of the untrammelled, what vast oriental simplicity led the Moorish architects to this purely optical enchantment, to these dreamy, unmaterial edifices, woven of lace, sheen, apertures, and kaleidoscopic patterns; this altogether worldly, sensual, luscious art actually quelled matter and transformed it into a magical veil.

Life is a dream. On these terms it will be realized that the Latin peasant and the Roman Christian had to sweep away this too refined and ornamental race. The European material and tragic sense of values had to prevail over the spiritualized sensualism of one of the noblest of civilisations.

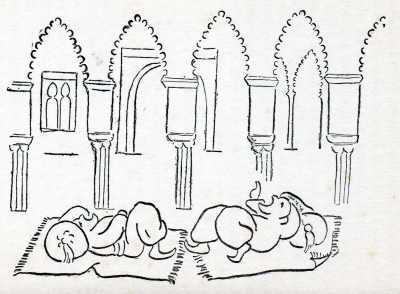

Let me add that, quite briefly, the difference between European buildings and Moorish architecture is implicit in the fact that Gothic and indeed, Baroque, are built for spectators, standing or kneeling, while Moorish architecture was clearly intended for spiritual voluptuaries who, while lying on their backs, revelled in these magical arches, ceilings, friezes and endless decorative arabesques which were vaulted above their heads to provide them with the inexhaustible means for dreamy contemplation.

And all of a sudden these fantastic, delicate patios, enclosed within the notched wall, are invaded by a flock of white pigeons; at this you realize, almost with amazement, the true meaning of this magical tectonic order; it is absolute lyricism.