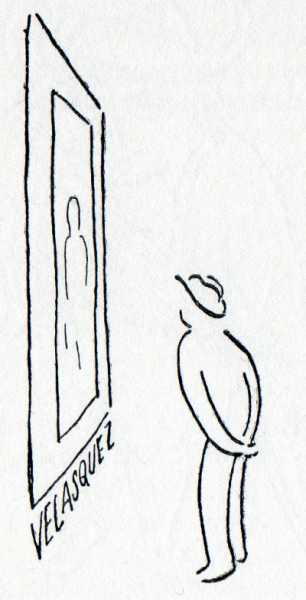

Chapter Seven - Velázquez o la Grandeza

Velázquez o la Grandeza

IF you want Velázquez you must go to Madrid, for one thing because most of his pictures are there, and then too, that is just the place, with its pomp in a sober setting, amid princely ostentation and plebeian hubbub, that city which is at once ardent and cold, where he seems to fit in almost as a matter of course.

If I were to sum up Madrid briefly, I should say that it is a city of courtly show and fitful revolutions; just notice how the people hold their heads: it is half grandeza and half doggedness. If I have any flair at all for cities and people, I should say that in the atmosphere of Madrid there is something like a gentle tension which causes a slight excitement, while Sevilla blissfully takes its ease, and Barcelona seethes in semi-concealment.

Thus, Diego Velázquez de Silva, knight of Calatrava, royal marshal and court painter of that pale, cold and strange Philip IV, belongs to that Madrid of the Spanish Kings by a twofold right.

First and foremost he has grandeur; he is so supreme that he is beyond all lies. But this is not the exuberant, golden grandeur of Tizian; there is in it a trenchant coldness, a delicate and yet unrelenting sense of detail, an uncanny sureness of eye and brain which rules the hand.

I imagine that his king made him marshal, not to reward him, but because he feared him: because the intent and penetrating eyes of Velázquez made him uneasy: because he could not bear this equality with the painter and he therefore raised him to the rank of grandee. So then it was a Spanish paladin who painted the pale king with the weary eyelids and frozen eyes, or the pale infants with rouge on their faces, poor, tightly laced puppets. Or the court dwarfs with dropsical heads, the palace jesters and fools, swaggering with grotesque dignity, a crippled and imbecile plebeian monstrosity unwittingly travestying the grandeur of the court.

The king and his dwarf, the court and its jester: Velázquez accentuated this antithesis too markedly and too consistently for it not to have its peculiar meaning.

The royal marshal would scarcely paint the court menials if he himself did not wish to. If there were nothing more in it than this, then at least there is one cruel and cold-blooded message: this is the king and the world he lives in.

Velázquez was too superb a painter merely to fulfil commissions; and too great a man to paint only what he saw. He saw too well not to allow his eyes to serve as a medium of vision for the whole of his clear and supreme intelligence.