Chapter Thirty-eight – Montserrat

SEEN from a distance, it is a sturdy, impressive mountain which, from the waist upwards, overtops the other hills of Catalonia; but the nearer you get to it, the more you are amazed, and you shake your head, till at last all you can do is to mutter: “Well, I’m hanged!” and “I’ve never seen anything like that before.” Which only goes to confirm the old experience that the things of this world are far more remarkable at close quarters than from afar.

For, you see, what from Barcelona looks like a compact range turns out a close quarters to be a mountain perched on columns; in fact, it looks more like a specimen of ecclesiastical architecture than a mountain. Below, there is a plinth of red rock, from which rocky pillars tower upwards; on top of them there is something resembling a gallery which supports a fresh row of huge columns; and above them a third storey of this immense colonnade hoists itself upwards to a height of more than six thousand feet. Well, I’m hanged; I must say, I’ve never seen anything like this before.

The higher the fine spiral path uncoils, the more it makes you hold your breath; below the steep precipice of Llobregat and above your head the steep towers of Montserrat; and between the two, as if it were on a projecting balcony, hangs a holy monastery and a cathedral and a garage for several hundred cars, motor-buses and charabancs, together with a hostel where you can lodge with the Benedictine monks in that monumental and bristling hermitage; and in this monastery there is a library such as perhaps no other monastery contains, which ranges from old folios in wooden and pigskin bindings, to a whole shelf of books about cubism.

But there is still the peak of the mountain, Sant Jeroni; you are taken there by an absolutely vertical funicular railway, which makes you think of a sardine-tin being hauled along a rope to the top of the church-steeple; but you take your seat in this tin, and try to look alert and adventurous, as if you were not frightened out of your wits at the possibility of being hurled to kingdom come.

And when you get to the top and pull yourself together, you do not know what you ought to look at first; so I will draw up a list of things for you:

1. The vegetation which, seen from below, looks like tufts of hair under the armpits of those huge upraised limbs, but at close quarters it proves to be a delightful crop of evergreen barberries and holly, box-tree and spindle-tree, rock-rose, myrtle and laurel and Mediterranean heather; I’ll be hanged if I’ve ever seen such a natural park as here on the mountain-top and among the crevices in these expanses of hard rubble which look as if they were moulded from flinty concrete.

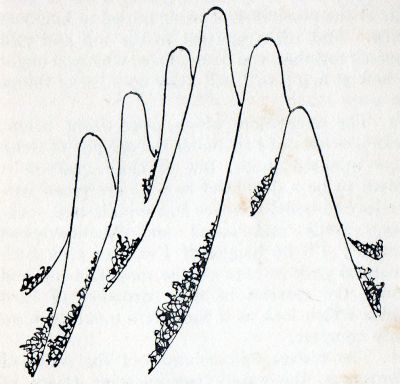

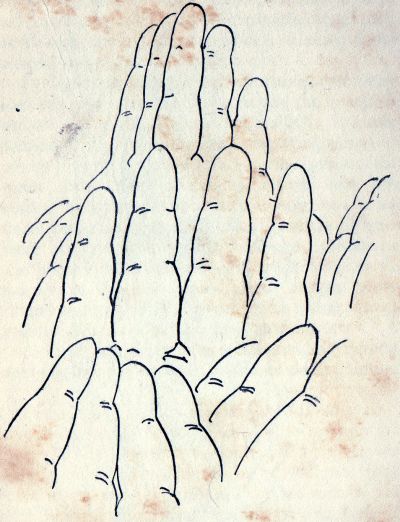

2. The towers and columns of the rocks of Montserrat, the naked, awe-inspiring steeps of the Evil Valley, which is supposed to have split apart on the day of Christ’s crucifixion. There are number of scientific theories as to what these rocks resemble; according to some, they are like sentries, according to others, a procession of monks in cowls, or flutes, or roots of extracted teeth. I myself call heaven to witness that they resemble upraised fingers clutched together as in prayer; and so Montserrat prays with a thousand fingers, avows with lifted fingers, blesses the pilgrims and makes a sign.

My own belief is that is was created and upraised above all the other mountains for this special purpose, and my belief is further, that it is now out of place, but I thought of this while sitting on the summit of Sant Jeroni, which forms the highest peak and, at the same time, the centre of this vast and quaint natural cathedral.

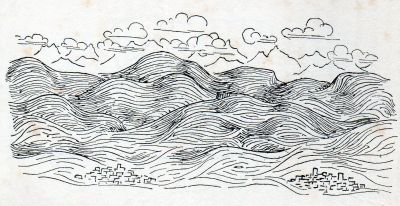

3. And then there is the surrounding country, earth rippling, farther than the eye can reach, in green and pink heights: Cataluña, Navarra, Arragon; the Pyrenees with sparkling glaciers; white townships at the foot of the mountains; queer, oval hills, so arranged to look like ruffled tresses though which a huge comb has been passed. Or rather, they look as if they were still marked by the furrowed imprint of the divine thumbs which kneaded this warm, russet region with a special creative zest.

Having beheld all this and marvelled thereat, the pilgrim set out on his homeward journey.