Chapter Thirty-four – Tibidabo

Tibidado - Barcelona

TIBIDABO is a hill above Barcelona; on the top there is a church, cafes and swings, and especially a view of the sea, the town and its surroundings; the sea in question gleams with a steamy haze, the town emits an uncommonly delicate sparkle of white dwellings, and its surroundings are tinged with a green and pink lustre.

Or from the Font del Lleó terrace, there is a beauty for you, the shining town between the warm surge of the hills and the sea, a vista as stimulating as light wine.

Or evening on the slope of Montjuich at the exhibition, when all the fountains, conduits and cascades, the frontages and turrets are set agleam with such an array of lights that you are at a loss to describe it, and all you can do is to look at it till your head begins to whirl.

But these fabulous items are incomplete without Barcelona itself; a rich city, as good as new, which rather flaunts its money, its industries, its new streets, shops and villas; there are miles and miles of them, left and right, and in the middle, as if at the bottom of a pocket, the old town manages to wedge itself in around a few ancient and venerable objects, such as a cathedral, a town hall and a Diputación, with its close and swarming streets, cut in two by the famous Rambla, where the populace of Barcelona jostles under the plane-trees to buy flowers, to ogle the girls and to start revolutions.

All in all, a brisk and pleasant city, blazoning forth its prosperity, rushing out to the surrounding hills, an ostentatious and flamboyant place, like its fanciful architect Gaudi, who so feverishly elevated his soul heavenward in the unfinished nave and the pine-cone turrets of that vast cathedral torso, Sagrada Familia.

And the harbour, dirty and noisy like all harbours, an enclosed zone of nocturnal resorts, dancing halls and shows, filled at nightfall with the clatter and the racket of all their mechanical orchestras, blatant with coloured lights, gross and rampant with its queer mob of stevedores, seamen, riffraff, plump wenches, rowdies and harbour dregs, a brothel larger than Marseilles, a low haunt more dubious than Limehouse, a sink of iniquity where earth and sea shed their scum.

And the working-class suburbs, where you see men with their clenched fists in their pockets, and rabid defiant eyes; let me tell you, this is very different from the free and easy dwellers in Triana; take a sniff, and you will discover something smouldering here.

At nightfall shadows range along towards the centre of the town; they wear espadillas on their feet and red belts round their waists; a cigarette clings to their lips and their caps are pulled down over their eyes. They are only shadows, but when you look closer, the form quite a cluster. A cluster of staring, dogged eyes.

And here in the middle of the city, are the people who refuse to be Spaniards; and in the mountains round about, peasants who are not Spaniards.

From the heights of Tibidabo it is a brilliant and prosperous city; but as you get nearer and nearer to it, you seem to hear the sound of rapid panting between clenched teeth.

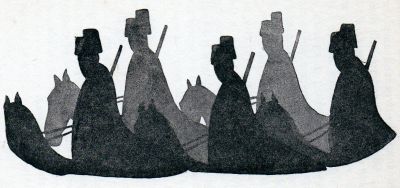

Meanwhile, Barcelona overflows with lights and amuses itself hectically; the theatres do not open until midnight, at two in the morning the dancing halls and other pleasure haunts are packed, the silent and sullen clusters loiter on the ramblas and paseos, and suddenly, noisily disappear when an equally silent and sullen posse of mounted gendarmes, with rifles ready in the saddle, come into view at the next corner.