Chapter Twenty-four – Lidea Ordinaria (Part Two)

Lidea Ordinaria (Part Two)

AND once again the corrida unfolds itself in all its dazzling beauty and horror, like a hunting dream. Once again the toreros flaunt their gilded mantlets and jackets, the gold-clad picadors enter on wretched, blindfold nags, and take up their positions where they await the bull, who, in the meanwhile, is kept busy by the toreros with their cloaks, the capering and dodging.

The toreros egg him on to meet the picador, who stretches out his long pike, while his blindfold nag shivers with fright and would like to rear, if it could manage such a feat. Now this particular bull was nothing loth, and with zest made a dash straight for the picador; he bumped his neck against the lance, and it was a marvel that he did not fling the picador from the saddle; but he only shook himself and started off again at a headlong gallop, caught the bony jade, rider and all, on his horns and hurled them on the planks of the barrier.

At the present day, by order of the dictator, the belly and chest of the picador’s nag must be covered with a mattress, so that although the bull generally knocks it over and lays it out, he rarely rips its flank open, as used to happen; all the same, the interlude with the picadors is brutal and stupid; you know, it simply doesn’t seem decent to watch that decrepit gelding convulsively struggling, or to drag it along to make it submit to the bulls terrific onslaught, then to set it on its legs again and hound it once more against the bull’s horns; for with the blunt spear these two picadors have to inflict three deep wounds on the bull, so that he may lose a little blood and be “castigado”.

The fight itself may be a fine spectacle; but the terror, reader, the terror of beast and man alike, is an appalling and ignoble sight. And when horse, rider and spear are mingled in a regular welter, the toreros come leaping forward with their cloaks and take away the snorting bull, who always wins this first skirmish – at the cost of an ugly wound between the shoulder-blades.

Then the picadors trot off, the bull becomes infuriated by the red linings of the cloaks, and the baderillos come trotting into the arena. They are, if anything, even more resplendent than the others, and in their hands they carry their javelins, or rather long wooden darts, decorated with paper frills and ribbons; they trip along the front of the bull, call him names, wave their arms and rush towards him to try and induce him to make a blind, rampageous attack with lowered head and outstretched neck.

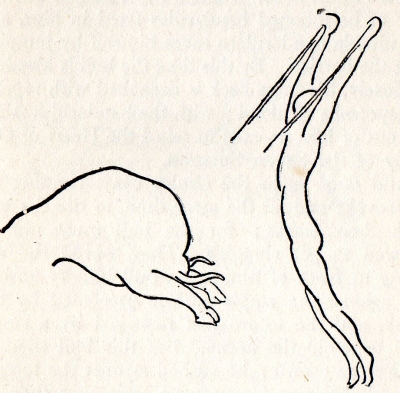

At the instant when the bull rushes out, the banderillo raises himself of tiptoe, arches his back like a bow, and, taking aim with the banderillas in his hands raised on high, waits. I must say there is something extremely fine about this easy, elegant, posture of a man facing a raging beast.

In the last fraction of the instant the two banderillas hurtle like lightning, the banderillero leaps aside and departs at a trot, while the bull jumps about in the queerest manner, try to shake away the two darts which are waggling to and fro in his neck.

After a while he gets another pair of beribboned banderillas fixed in him, and the nimble banderillero saves himself by jumping over the barrier. By this time the bull is bleeding profusely, his huge neck is drenched with regular honeycombs of blood; with the banderillas sticking out of him he calls to mind the Heart of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows.