Chapter Twenty-three – Lidia Ordinaria (Part One)

Lidia Ordinaria (Part One)

THE second part of the corrida was a fight on ordinary lines, which is more dramatic, but also more distressing. I should not like to judge all bull-fights on the strength of that one, because it was an unlucky day.

The very first bull, when the banderillas reached him, went mad and made a stubborn attack; but the shouting crowd did not want him to get tired at the very start; so there was a blare of trumpets, the arena was emptied, and Palmeño, the gold-bespangled espada, went to pink the bull. But the animal was still too quick; at the first onset he gored Palmeño in the groin, tossed him in a semicircle over his head, and dashed up to his powerless body. I had previously seen an infuriated bull tearing and trampling on a cloak which had been cast aside. It was a moment when my heart really missed a beat.

As this particular instant a torero arrived at the scene with a cloak and hurled himself straight at the horns of the bull, whose eyes he covered with a mantilla; he then made the attacking bull follow him.

Meanwhile two chulos lifted up the hapless Palmeño and carried the handsome, unconscious fellow of at a canter. “Prognóstico reservado” was the report which the next day’s papers published about his injuries.

Now if I had left immediately after this incident, I should have been haunted by the memory of one of the most impressive sights I have ever witnessed: a chulo, whose name was not even mentioned in the papers, exposed his stomach to the bull’s horns, to get him away from the wounded matador; without hesitation he diverted the madly attacking bull towards himself, and at the last instant just managed to leap out of his way; another torero had already arrived, and with a cloak was attracting the bull towards him, so that the first man could wipe the sweat from his forehead with a gilt-diapered sleeve. Then the two ornamented men withdrew, and a new espada, sword in hand, took the place of the crack performer who had been wounded.

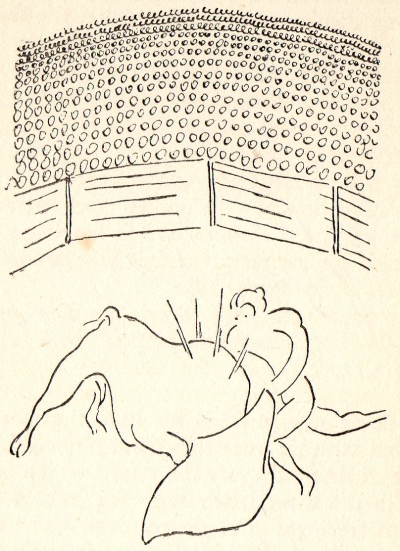

The Matador sobresaliente was a man with a long, dismal face, and was evidently no favourite. He proceeded to take charge of the bull, who was what might be called a bad hat. From this moment onward the corrida degenerated into a shocking display of butchery, when the frenzied crowd by their shouting and whistling fairly hurled the unpopular espada right at the horns of the savage animal; and with clenched teeth, as if death was in store for him, the man went too, and with an uncertain hand pinked the bull.

The bull dragged away the sword which had got fixed in the wound, where it was jerking to and fro. A fresh shout of disapproval. The toreros ran up to keep the bull busy with their cloaks.

The mob hounded them on with fierce shouts: it was eager for the bull to die a chivalrous death, come what may. The pale matador set out once again to slay with sword and cudgel, in accordance with the rules of the game; but the bull then would not budge an inch, and stood still with upraised head, his neck bristling with banderillas, and garbed, so to speak, with a mantle of blood.

The espada, with the point of his sword, made him lower his head so that he could pierce his shoulder, but the bull stood there mooing like a cow. The toreros flung cloaks over the banderillas embedded in his neck, thinking that the fresh pangs of pain would goad him out of his glum obstinacy; but the pain made the bull bellow and pass water, and then he scraped his feet, as if he wanted to hide himself in the ground.

At last the matador got him to lower his head to the ground, and pinked the motionless animal; but not even this wound finished him off; the puntillero also had to fling himself like a weasel upon the bull’s neck, and ran him through with a dagger.

Amid the frantic laughter and outcries of twenty thousand people the lanky matador, all glittering with gold, departed with a small, shaggy tuft of black hair in the nape of his neck, as tradition enjoins; his sunken eyes were fixed on the ground. Nobody shook his hand when he passed the barrier; and this luckless man had to tackle three more bulls.