Chapter Twenty-two – Corrida (Part Three)

Corrida (Part Three)

NOW the blue, showy Portuguese cantered into the circle, galloped around the arena, turned and saluted with his headgear; his mount moved even more trippingly, and it lifted its legs even more prettily, as prescribed by the riding academy.

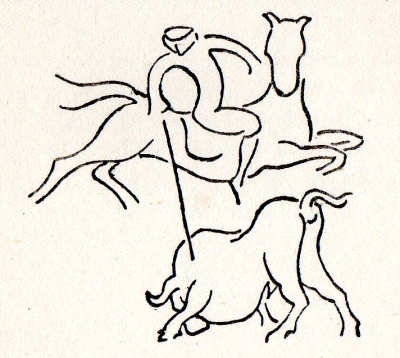

The black bull which burst through the gate was a bad-tempered, stubborn beast; he stood there hunched up, with his horns prepared for a sally, but he would not let himself be enticed to make a dash; it was only when the trembling horse trippingly marked time a few paces from him, that he rushed out as if propelled by a catapult. He was so sure of what he was about, that he almost turned a somersault on the spot where he expected the impact with the horse’s chest; but at the same instant that his black bulk started moving, the horse, turning round in response to the rider’s knees, galloped off like an arrow from the bow-string, and fairly flew onwards, then turned while galloping at a headlong pace, and trotted back in gavotte time to the snorting bull.

Never have I seen a rider so perfectly blended with his horse; a rider who sat motionless in the saddle whether galloping or jumping, who could turn his horse in a fraction of a second, pull him up short, make him rear, get him, while at the gallop, to tackle a high jump, a long jump and other capers which I do not even know the names of; and all the time he held the reigns lightly in one hand as if they were a cobweb, while in the other lurked the murderous barb of the lance.

But now just bear in mind that this feat of horsemanship was performed by a rococo dandy, face to face with the horns of an infuriated bull – it is true that in this particular instance the sharp tops of the horns were made safer by rubber nobs; bear in mind, I say, that he slipped away, jumped aside and attacked, darted off like an arrow and bounded back like a piece of Indian rubber, grazed the bull with his spear which racing along at full speed, broke the shaft of his lance, and then defenceless, with the fuming beast full tilt after him, cantered to the barrier for a new lance. At the gallop he thrust three spears home, and then, taking no further notice of the bull, pranced out into the arena; the bellowing animal still had to be attended to with a sword, and, to wind him up with, the puntillero had to run a dagger through him. It was a revolting piece of butchery.

The third bull was dealt with by two competitors. The Portuguese had the first spear; while he was dallying in front of the bull’s uncovered horns, the Andalusian was marking time on his colt, ready to join the fray at a moment’s notice. But the third bull meant business; truculent and astoundingly quick, he did not stop attacking from the moment when, amid clouds of dust and sand, he dashed into the arena. Lunge followed lunge; this bull was quicker than the horse, and chased the rider all over the arena.

But suddenly, he took it into his head to have a go at the expectant Andalusian. The Andalusian turned his horse round and fled; the bull stubbornly followed him and caught him up. This is the moment when the rejoneador, to protect himself and his horse, lets fly with his spear to stop the bull’s little game; but in this case, the first spear belonged to the Portuguese.

The Andalusian lowered his outstretched spear, then, with heaven only knows what effort of strength, dragged the horse aside, and scurried away amid tremendous cheering and shouting; for the Spaniards appreciate a feat like that.

The Portuguese took charge of his bull and led it forward in a gallop; while racing along he took aim with his lance, but the bull jerked its head, and the spear flew a long way off into the sand.

It was now the Spaniard’s turn; he took charge of the bull and tried to tire him out by letting himself be chased all over the arena. Meanwhile Don Joao came back with a fresh horse, and looked on.

This bull seemed to have a strategy of his own; he hounded the Andalusian to the barrier, attacking his left flank. Suddenly the audience rose up in their excitement; the bull had now caught up the rider on his uncovered left flank; at this, the blue rococo dandy dashed out full tilt against the bull, the horse reared and jumped aside, the bull jerked its head towards its new opponent who now flinched back; but at that instant the Andalusian had already twisted his horse round and thrust the lance into the bull’s neck, like a knife into a lump of butter.

Whereupon the crowd stood up and cheered; and I, who never, not even in books, can find nothing attractive about toying with death, for death is neither a joke or a spectacle – I had a lump in my throat; of course, this was the result of horror, but of admiration as well.

For the first time in my life I beheld chivalry, in accordance with the formula: with arms in hand, face to face with death, risking life for the honour of the thing.

Reader, I cannot help myself: there is something in it; something great and splendid. But not even the third spear finished off this astounding bull; again a man had to come rushing over with a dagger – and the crowd swarmed over the arena, which lay there clean and yellow amid the blue Sevillan Sabbath.