Chapter Eight - El Greco o la Devocion

El Greco o la Devocion

YOU must search for Domenica Theotocopuli, known as El Greco, in Toledo; not that he fits in there more than anything else, but the place is full of him and, besides, in Toledo nothing surprises you; not even El Greco.

A Greek by origin, a Venetian in colour, he was Gothic in his art, and by a whim of history he cropped up when Baroque was let loose. Imagine Gothic verticalism which has encountered a blast from a Baroque whirlwind; the Gothic line warps, and a surge of Baroque darts up and permeates the perpendicular eruption of Gothic, at times is seems as if the pictures were cracking with the tension from these two forces. There is such an impact that it distorts the faces, warps the bodies and flings garments upon them in heavy tempestuous folds; clouds uncoil like bed-linen fluttering in a tempest, and through them penetrates an abrupt and tragic light, enkindling colours with an unnatural and eerie intensity. As if judgement-day had come, when signs and tokens are revealed in heaven and on earth.

And just as in Greco himself two types of form merge into each other, so also you feel in his pictures to conflicting elements which goad each other on to extreme lengths: a direct and pure vision of God, such as hallowed art up to the Gothic period, and a rampant mysticism by which all the human, all to human Catholic Baroque was emotionally stimulated. The old Christ was not the Son of Man by God Himself in His glory.

Theotocopuli the Byzantine carried the old Christ with him; but in Baroque Europe he discovered the humanized Christ who had been made flesh.

The old God held sway sublimely, relentlessly and a little rigidly in his mandorla; the Baroque and the Catholic God amid his angel choirs glided to earth in order to clutch at the believer, and draw him within the curving range of his glories.

Greco the Byzantine came from the basilicas of holy science into the churches with their loud surges of organ music and frenzied processions; I should have imagined that this meant rather a lot to him; but amid the uproar he did not lose the thread of his own prayers, and he himself began to shout in a dire and unnatural voice.

In him there developed what might be called a frenzy of belief; this mundane and material tumult did not assuage him; he had to shout it down with a more shrill and vehement outcry.

How odd: this eastern Greek surmounted western Baroque by raising it to an ecstatic pitch of emotion and getting rid of its exuberant and muscular human attributes. The old he grew, the more did he dehumanize the figures, lengthening the bodies out of all proportion, emaciating the faces with the gauntness of martyrdom, and fixing the eyes upward with a wide-open stare upon a pillar. Up, heavenward! He removes reality from his colours; his darkness hisses and colours are enkindled as if illuminated by lightning.

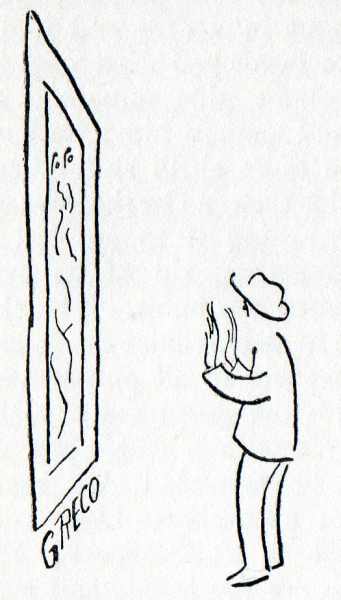

Hands which are too fragile and incorporeal are uplifted in amazement and terror, the stormy heavens are rent asunder and the shrill lament of awe and belief reaches the ancient God.

Yes, this Greek was an overwhelming genius; some assert he was mad. Every man whose eyes become feverishly fixed upon his own visions is a little mad, of at least he lapses into mannerisms because he takes from himself and from nowhere else the material and form of his visions.

In Toledo foreigners are shown la Casa de Greco; I cannot believe that this charming little house with the trim tiled garden belonged to the queer Greek. It has too mundane a smile for that, and it also looks too prosperous. We know that the only heritage which Greco left to his son was two hundred of his paintings. Evidently at that time there was no very brisk demand for the retables of the eccentric Cretan.

It is only to-day that the spectators crowd round these pictures in devout admiration; but they are people without faith, who are in no way startled by the shrill and despairing outcry of the Greek’s piety.