Chapter Eighteen – Triana

Triana

TRIANA is the gipsy and working-class quarter of Seville on the other side of the Guadalquivir; besides this, Triana is a special kind of dance, as well as a ditty if its own kind, just as Granadinas are typical songs of Granada, Murcianas of Murcia, Cartageneras of Cartagena and Malagueñas of Málaga.

Just imagine Brixton having it own sort of dance and Golders Green it national poetry; of Birmingham having an entirely different musical folk-lore from Ipswich, and Winchester, let us say, being distinguished by a particularly passionate and eccentric dance, I am not aware that Winchester has gone to such lengths yet.

Of course, I trotted off to have a look at the gypsies of Triana; it was Sunday evening, and I expected to find Gitanas dancing there at every street-corner to the sound of the tambourine; I expected too that they would drag me to their camp and that terrible things would befall me; still, I resigned myself to my fate and off I went to Triana.

Nothing whatever happened; not that there were any lack of gypsies, male and female, there; the place swarms with them, but there is no camp. There are only some tiny cottages with clean patios, with a regular gipsyish abundance of children, mothers sucking their babies, almond-eyed girls with a red flower in their blue-black hair, slender gipsy-lads with a rose between their teeth, a peaceable Sunday crowd taking its ease on the doorsteps.

I, too, took my ease among them and hurled almond-eyed glances at the girls there. I can testify that most of them are of a pure, handsome Indian type, with their eyes just a trifle aslant, with olive-coloured skin and fine teeth; moreover, the movement of their croup is even more supple than that of the girls in Seville. That must be enough for you; it was enough for me in that melting night in Triana.

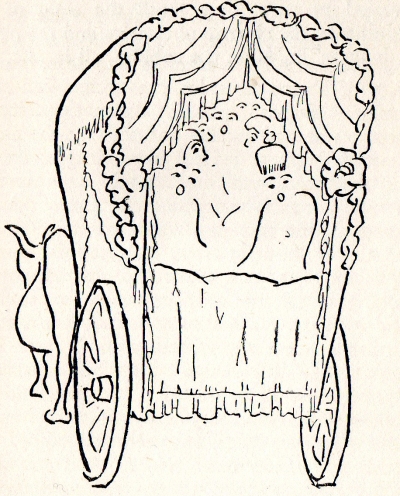

And because I was satisfied with little, the local deity of Triana rewarded me with a full-blown romería. Suddenly, in the distance a clatter of castanets became audible, and through the narrow street of Triana glided a high car, dragged by oxen and festooned with wreaths and an abundance of tulle curtains, canopies, trimmings, flounces, drapery, veils and all sorts of other falls, and the nice white body of the car was full up inside with girls who were clicking on their castañuelas and singing at the top of their voices, as people to sing in Spain.

I solemnly assure you that this garnished car, illuminated with a red fancy lantern, had the strange voluptuous aspect of a marriage-bed filled with girls. Each one in turn obliged with a loud seguidilla, while the rest kept time with their clattering castanets, clapped their hands, and made shrill noises. And round the next corner a similar car was gliding along with a load of bedizened, shouting and clattering girls.

And then there was a carriage drawn by a team of five donkeys and mules, driven by caballeros in Andalusian sombrero's. And there were other caballeros on prancing horses. I asked the bystanders what this meant, and the said it was the vuelta de la romería, ¿sabe?.

I must explain that a romería is a pilgrimage to some sacred spot in the vicinity, to which the populace of Seville, especially the populace of both sexes, goes on foot and in conveyances; and on the girls’ petticoats there are broad flounces of whatever they’re called, and the cackle like a cartload of sparrows.

And when amid the clatter of castanets, the merry romería had disappeared in the street of Triana, the regional secret of the castañuelas was revealed to me: they recall the song of the nightingale, the chirrup of crickets and the clatter of donkeys’ hoofs on the cobbles, all in one.