Chapter Eleven - Andalucía

Andalucía

I must frankly admit that when I woke up in the train and looked through the window, I hadn’t the faintest idea where I was; alongside the railway-line I saw something which looked like a quickset hedge, behind it brown, flat fields, and from them protruded, here and there, sparse and jaded-looking trees.

I had a strong and comforting impression that I was travelling somewhere between Bratislava and Nové Zámky, and I began to give myself a wash and brush up, lustily whistling ‘Kysúca, Kysúca’ and other songs appropriate to the occasion.

When, however, I had exhausted by supply of Czech songs I perceived that what I had taken for a quickset hedge was a dense aftergrowth of opuncias, six feet high, plump aloes and a sort of stunted palm tree, probably Chamaerops, and the jaded trees were, I found, date-palms, while the brown tilled plain was apparently Andalucía

So you see how it is; if you were travelling across the tilled pampas, the Australian maize-fields, the wheat-leaden expanses of Canada, or heaven knows where else, it would be exactly like the country near Kolín or Breclav.

Nature is infinitely various, and as regards man, he differs in hair, language and a thousand sundry ways of life; but the farmer’s work is the same everywhere, and arranges the face of the earth in the same straight and regular furrows.

The houses are different, and so are the churches; why, even the telegraph poles are different in each country, but the tilled field is the same everywhere, whether in the neighbourhood of Pardubice or of Seville. There is something great and also a trifle monotonous about this.

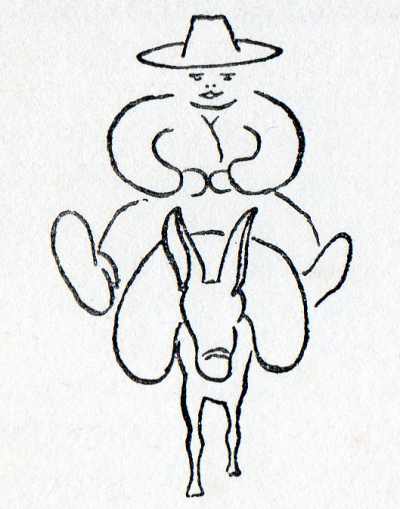

But I must add the farmer of Andalusía has not the same broad and clumsy gait as our; The Andalusian farmer rides on a donkey, which makes him look excessively Biblical and droll.