Chapter Five - Toledo

Toledo

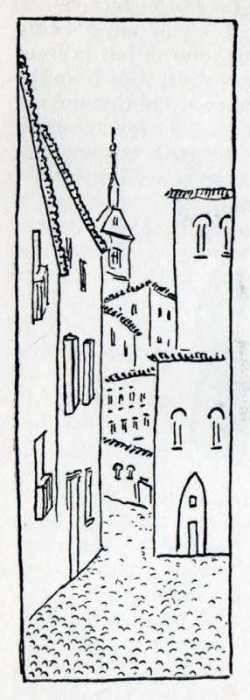

YOU have here a brown, warm plain, studded with villages, donkeys, olives and dome-shaped walls; from this plain, without any warning, a great granite rock thrusts itself, and all the objects on it are squeezed together, one on top of the other; and below in the chasm of brown rocks flows the brown Tajo.

As regards Toledo itself, I really don’t know whether to begin with the ancient Romans or the Moors or the Catholic Kings. But as Toledo is a mediaeval town, I will begin with what a mediaeval town undoubtedly begins with, viz, the gates.

For instance, Toledo has a gate known as Bisagra nueva, rather in the style of Terezín, with a Habsburg double eagle which is distinctly above life-size; it looks as if it led to our Terezín or Josefov, but contrary to all expectation it debouches into a quarter which is called Arrabál and looks it, too.

Whereupon you are in front of another gate which is called the Gate of the Sun, and looks as if you had been set down in Bagdad, but instead of that the Moorish portal leads into the streets of the most Catholic of towns, where every third building is a church with a bloodstained Jesus and an ecstatic retable of Greco.

Also you wander through winding Arab by-streets, gaze through gratings into Moorish courtyards which are called patios and are inlaid with Toledam majolica, you keep clear of donkeys laden with wine or oil, you peep at the beautiful harem-gratings of the windows and altogether you trudge along as if in a dream.

You might come to a standstill at every seventh step; here is a Visigoth pillar and there a Mozareb wall; here a miraculous Virgin Mary, who finds a wife or a husband for all, and there a Mudejar minaret and renaissance palace like a fortress, and Gothic windows, and a façade encrusted with gold and gems in the estilo plateresco, and a mosque, and a street so narrow that a donkey can only get through if he squeezes his ears back; glimpses of shady majolica courtyards where fountains gurgle amid flower-pots; glimpses of the sky; glimpses of churches frantically decorated with everything which can be carved, hewn, moulded, damascened, hammered, painted, embroidered, tricked out with filigree, gilded and set with precious stones.

Thus you can stop at every step, as in a museum; or you can walk along as in a dream, for all this, the products of a thousand years, marked with the flaming script of Allah, the cross of Christ, the gold of the Incas, the life of diverse periods, gods, civilisations, and races, is, after all, a fantastically uniform thing; so many periods and civilisations enter the hard clutch of the Toledan rock. And then, in one of the narrowest streets, from the barred window of a human cage a bird’s eye view of Toledo is revealed to you: one single surge of flat roofs beneath the blue sky: an Arab town, glistening in the brown rocks, gardens on the roofs, and delightful, languorous patios with an intimate and comely life of their own.

But if I were to take you by the hand and show you over everything that was revealed to me in Toledo, I suppose I should first lose my way in those winding poverty-stricken streets. Not that I should regret that, for their too we should have to keep clear of the donkeys, pattering over the cobbles with their nimble hoofs, we should see the open patios and the majolica staircases and moreover we should encounter people.

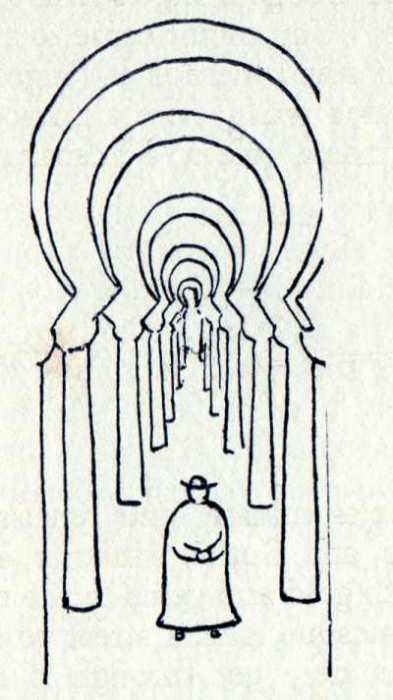

Perhaps here I should find that Mudejar chapel, white and chilly, with its fine horse-shoe arches; a little further on is a rock which falls sheer into the Tajo, and the synagogue del Transito, bestrewn with fragile and curiously refined Moorish ornamentation.

And churches: thus, the one with Greco’s “Burial of the Count Orgaz,” or the one with that magnificent Moorish cloister, just like a dream. And the hospitals with palatial courtyards. There is one of them in front of the gate, and in it there are poor nuns with huge wing-shaped headgear and a crowd of orphans holding hands, like a long snake, as they trudge along to church singing “Antonino” or “Santo niño” or something of that sort; and for their use there is an old dispensary with beautifully enamelled pots and flagons labelled : “Divinus Quercus” or “Caerusa,” “Sagapan” or “Spica Celtic,” remedies which have stood the test of time.

Now concerning the cathedral, I am not sure whether I was there or not; for as just in front of it I sampled the Toledan wine, wine from the Vega plain, a drop of wine so liquid that it flows down the throat all by itself, and a wine as thick as a curative oil, I am not prepared to swear that I did not dream about it or muddled it up somehow. There was so much of it; I know that there were exquisite miniatures and fantastic ciboria, gratings which reached to the skies, carved retables with a thousand statues, jasper balustrades, canonical chairs carved from above, from below, from the middle and from the back, pictures by Greco, organs rumbling in some place unknown, prebendaries as stout and desiccated as stockfish, chapels inlaid with marble, painted chapels, black chapels, golden chapels, Turkish banners, canopies, angels, tapers and vestments, impassioned Gothic and impassioned Baroque, plateresque altars and a churrigueresque Transparency absurdly bulging beneath a dark, lofty, vaulted dome, a medley of senseless and amazing things, of glowing lights and awe-inspiring darkness – well, perhaps I only dreamt about it; perhaps it was only a dreadful, confused dream in the wicker chair of a church, perhaps it is not even possible for any religion to need all these things.

So, caballero, go for a stroll in the streets of Toledo to clear your head of this gluttonous wallowing in works of art. You, shapely windows, small Gothic arches, Gothic and Moorish ajimez; you, hammered rejas, houses with battlements, patios with children and palm trees, tiny courtyards inlaid with azulejos, streets of Moors, Jews and Christians, where it is a joy to loiter in the shadows, caravans of donkeys - in you, I say, and in many, many tiny details there is just as much history as in any cathedral, the best museum is the street of living people.

I had almost said that here you imagine yourself straying into another age, but that is not true. The truth is stranger; there is no other age; what was, is.

And if this caballero were begirded with a sword, and that priest yonder were to expound the scriptures of Allah, and that girl was the Jewess of Toledo, it would not strike you as being a whit more curious and remonte than the walls of the Toledan streets.

If I were to enter another age it would not be another age; it would be only a bewilderingly fine and high adventure.

Like Toledo. Like the Spanish land.