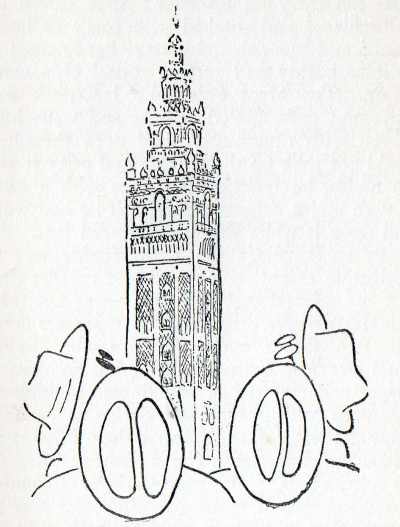

Chapter Fourteen - Giralda

Giralda

THE Giralda is the landmark of Seville; it is so high that it is visible from every direction. If in the course of your globe-trotting you perceive, high above the house-tops, the gallery and turret of the Giralda, why, you can be certain you are in Seville, for which you may thank your lucky stars.

Now the Giralda is a Moorish minaret with Christian bells; it is begirt with all the beautiful devices of Arab decoration, and right on the top of it there is a statue of Faith, while the lower part is constructed of Roman and Visigoth ashlars.

That is just like Spain as a whole; it has Roman foundations, Moorish pomp, and a Catholic mind. Here Rome left only a little of its urban civilisation, but bequeathed something more permanent – the Latin farmer, which implies the Latin language. And this provincial Latin rusticity was assailed by the highly developed, luxurious, almost decadent culture of the Moors.

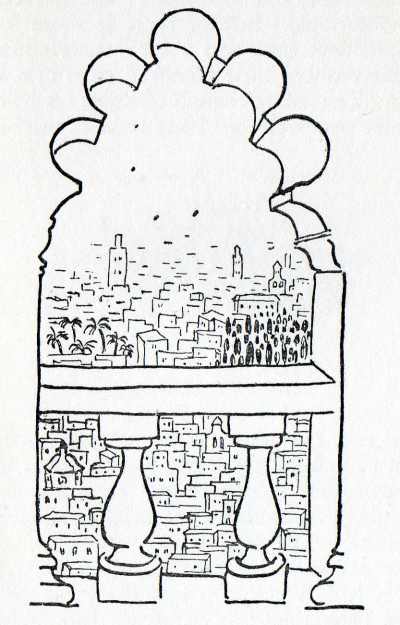

In its way it was a paradoxical culture; even in the highest stage of its refinement it retained a nomadic imprint. Where the Moors built castles and palaces you will detect signs that they were originally tent-dwellers.

The Moorish patio is a cosy representation of an oasis; the gurgling fountain in the Spanish courtyard, to this very day still gratifies the desert dream of cool springs; the garden, represented by the contents of the flower-pots, is a portable garden. The tent-dweller packs up his home and all his luxuries so that he can load them on asses; that is why his home is made of textiles and his luxuries are of filigree.

His tent is his castle; it is garnished with every pomp and splendour, but it is a pomp which a man can carry on his back; it is woven and embroidered and stitched with goat’s or lamb’s wool; and Moorish architecture has retained the delicate beauty and surface appeal of a woven fabric.

The Moor even built lace-work archways and embroidered ceilings and walls interwoven with ornaments. And even though he could not pack up the Giralda and carry it away on mules, he bedecked his walls with a carpet pattern and a delicate fabric as if he had woven and sewn it while sitting of crossed legs.

And when subsequently the Latin farmer and the Visigothic knight with sword and crucifix drove out of the oriental sorcerer, they never got rid of this richly woven dream, the Gothic estilo florido, the Renaissance estilo plateresco the Baroque estilo churrigueresco are nothing but architectural diaper and embroidery and filigree quilting and lace-work, which covers and, dream-like, conceals the stone walls and transforms them into magical glistening draperies.

The Nation perished but its culture lives. This most Catholic of countries has never ceased to be Moorish. All this and many things you could see with your own eyes on the Giralda of Seville.

And from the Giralda you can see the whole of Seville, so white and shinny that it makes your eyes ache, and pink with its flat, tiled house-tops braided with faience cupolas and belfries and battlements, palm-trees and cypresses; and right below, the huge, almost monstrous roof of the cathedral, an eruption of pillars, Gothic turrets, buttresses, groins and campaniles, and all around, farther that the eye can see, the green and gold plan of Andalusia, a-sparkle with glistening homes.

But if your sight is good, you will see even more; you will see families at the back of the patios, gardens on balconies and terraces and flat house-tops, wherever there is room for the smallest flower-pot, and women watering flowers of whitewashing their blanched cube of a house with a nice creamy coat of lime; as if in this life there were nothing else to think of but beauty.

And now we have the white town before us, let us make a pilgrimage to two places, which are particularly worthy of respect, and which are adorned with a whole set of masterly and worshipful works.

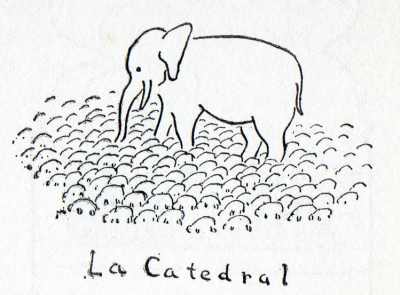

The first is the Cathedral. Every proper cathedral has two functions. To begin with, it is so big that it is entirely cut off from human habitations; it stands in their midst like a sacred elephant among a herd of sheep, isolated and alien, a divine eminence projecting from the human ruck.

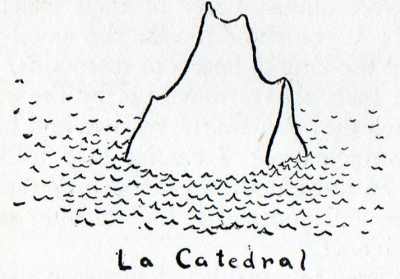

And in second place, as soon as you enter it, you find one huge open space amid the entrails of the town, larger in area than a market-place, larger than a city square; when you arrive there from narrow lanes, yards and household dwelling-rooms it is like reaching a mountain peak; these pillars and vaulted roofs do not enclose a space, but with an ample sweep they extend it, thrusting a broad and high outlet amid the rabble of a medieval town. Here, my soul, heave a sigh of relief; in the name of God you can take a deep and soothing breath.

But at this point of time I cannot tell you everything that was inside. Alabaster altars and vast lattices and the tomb of Columbus. Murillo and wood carvings, gold and traceries, marble and Baroque and retables and pulpits and many other Catholic objects which I did not even see; for I looked at what surmounted it all, the five large, steep naves, quite a divine naval display, a sublime fleet swimming above the lustre of Seville; in spite of all the art and culture amassed within its flanks, it contains an abundance of free and sacred space.

The other spot is the ayuntamiento or town hall. The exterior of Sevilla town hall is fairly plastered with relief and cornices, festoons and medallions and garlands, pilasters, caryatides, scutcheons and masks; and inside, from ceiling to floor it is bestrewn with wood-carvings and canopies, gildings, faience, stucco and every variety of trappings such as the masters of every guild could devise.

It is ostensibly done, and suggests that the city fathers were almost naive in their eagerness to show off; it somehow recalls the good-natured dignity of the king of hearts or diamonds. These old town halls always move me by the emphasis with which they declare the renown and brilliance of the municipality; I cannot help feeling that in them an ancient urban democracy established its throne and adorned it like a an altar or like a royal residence.

Now when present-day democracy can afford a palace, it is a bank or a commercial building. In less progressive times it used to be a minister or a town hall.