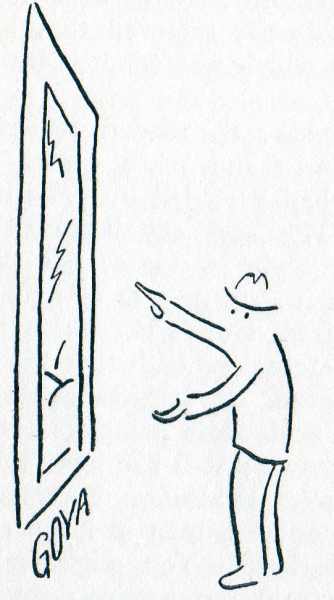

Chapter Nine - Goya o el Reverso

IN the Prado in Madrid there are dozens of pictures and hundreds of drawings by him; and so for the sake of Goya, if for nothing else, Madrid is a great place for a pilgrimage. Neither before nor after him was there a painter who pounced upon his age with so ample a clutch, with such intense and ruthless verve, and portrayed it, seamy side and all; Goya is not realism, Goya in onslaught; Goya is revolution; Goya is a pamphleteer multiplied by a Balzac.

His most exquisite work: designs for gobelins. A rustic fair, children, paupers, an open-air dance, an injured bricklayer, a brawl, girls with a jug, a vintage, a snow-storm, games, a working-class wedding; sheer life, its joys and sorrows, playful and evil scenes, a solemn and also a blissful spectacle; such teeming life, as lived by the people, had never before surged forth in any cycle of paintings.

It produces the effect of a folk-song, a frisky jota, a winsome eguidilla; it is a specimen of rococo, but now quite humanized; it is painted with a particular delicacy and relish which is surprising in so fierce a painter as this. Such is his attitude to the people.

Portraits of the Royal Family: Carlos IV, bloated and listless, like a bumptious, dull-witted jack-in-office; Queen María Luisa, with rabid and gimlety eyes, an ill-favoured harridan and an arrant virago, their family bored, brazen and repulsive. Goya’s portraits of kings are not far short of insults. Velázquez did not flatter; Goya went as far as to laugh. Their Highnesses to scorn. It was ten years after the French Revolution, and a painter, without turning a hair, told the throne what he thought of it.

But a few years later there was another revolution: the Spanish nation flung itself tooth and nail upon the French conquerors. Two astounding pictures by Goya: a desperate attack by the Spaniards on Murat’s mamelukes, and the execution of the Spanish rebels. These are specimens of reporting, which for sheer genius and emotional eloquence, have not their equal in the whole history of painting; at the same time Goya, as a mere incidental, achieved that modernity of composition which was adopted by Manet sixty years later.

Maya desnuda: the modern revelation of sexuality. A barer and more carnal nudity than any which had preceded it. The end of erotic pretence. The end of allegorical nudity. It is the only nude by Goya, but there is more exposure in it than in tons of academic flesh.

Pictures from Goya’s house: it was with this appalling witches’ sabbath that the artist decorated his house. It consists almost entirely of mere black and white paintings feverishly flung on to the canvas; it is like hell illuminated with livid flashes of lightning. Sorceresses, cripples and monstrosities: man in his dark wallowings and his bestiality. You might say that Goya turned man inside out, peering through his nostrils and his yawning gullet, studying his misshapen vileness in a distorting mirror. It is like a nightmare, like a shriek of horror and protest. I cannot imagine that this caused Goya any amusement: he more likely struggled frenziedly against some of it.

I had an uneasy feeling that the horns of the Catholic devil and the cowls of the inquisitors protrude from his hysterical inferno. At that time the constitution had been abolished in Spain and the Holy Officium restored; from the convulsions of the civil wars and with the help of the fanaticized mob the dark and bloody reaction of despotism had been installed. Goya’s chamber of horrors is a ferocious shout of disgust and hatred. No revolutionary ever affronted the world with so frantic and virulent a protest.

Goya’s sketches: the feuilletons of a tremendous journalist. Scenes from live in Madrid, weddings and customs of lower classes, chulas and beggars, the very essence of life, the very essence of the people; Los Toros bull-fights in their chivalrous aspect, their picturesque beauty, their blood and cruelty. The Inquisition, a fiendish church mummery, fierce and caustic pages from a lampoon; Desastres de la Guerra, a fearful indictment of war, a document for all time, pity which is truculent and ferocious in its passionate directness; Caprichos Goy’s wild outbursts of laughter and sobbing at the hapless, ghastly and fantastic creature which arrogates an immortal soul to itself.

Reader, let me tell you that the world has not yet done justice to this great painter, this most modern of painters; it has not het learnt the lesson he teaches. This harsh and aggressive outcry, this violent and thrilling quintessence of mankind; no academic dullness, no aesthetic trifling; when a man can “see life steadily and see it whole” really see it, I mean, then he is the doer of deeds, he is a fighter, an arbiter, a firebrand. There is a revolution in Madrid: Francisco Goya y Lucientes is erecting barricades in the Prado.