Chapter Seventeen - Mantillas

Mantillas

ALL that follows is intended in honour and praise of the ladies of Seville. They are petite and dark, dark-haired, with dark frisky eyes, and mostly in dark attire; they have tiny hands and feet, as required by the old lyrics of chivalry, and they look as if they were just on their way to confession, that is, they are saintly and rather sinful in appearance.

But what gives them particular splendour and dignity is the peineta, the lofty tortoise-shell comb, with which every lady in Seville is crowned; a sumptuous and triumphal comb, like a crown or a halo. This ingenious superstructure transforms every dark chiquita into a tall, grand lady; with a thing like that on her head she just has to walk proudly, to carry her head like a sacrament and to let only her eyes dart about, which accordingly the ladies of Seville do.

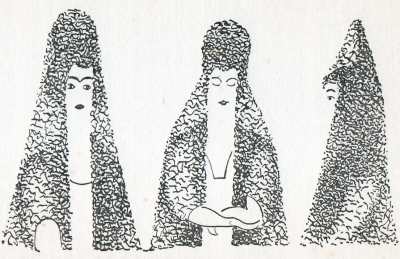

The second and even greater glory of the ladies of Seville is the mantilla, a lace wrap flung across the queenly comb; the mantilla, which is black or white, like the veil of the Muslim women, the cowl of the penitent, the mitre of the pontiff and the helmet of the conqueror; the mantilla which serves to crown woman and, at the same time, to conceal her and make her shimmer more alluringly. Never have I seen women wearing anything more dignified and subtle than this garb which blends nunnery, harem and the veil of the beloved.

But allow me to stop and extol these women of Seville. What self-assurance, what national pride these dark chulas must have to make them prefer the ceremonious and antique peineta and mantilla to all enticements of the world’s fashions.

Seville is by no means a village; Seville is a rich, vivacious city, the very air of which is amorous; if the ladies of Seville keep to their mantillas, that is firstly because it suits them, and secondly because they set store by being Spanish beauties in all their antique renown; but the chief think is that it suits them.

But allow me to stop and extol these women of Seville. What self-assurance, what national pride these dark chulas must have to make them prefer the ceremonious and antique peineta and mantilla to all enticements of the world’s fashions.

Seville is by no means a village; Seville is a rich, vivacious city, the very air of which is amorous; if the ladies of Seville keep to their mantillas, that is firstly because it suits them, and secondly because they set store by being Spanish beauties in all their antique renown; but the chief think is that it suits them.

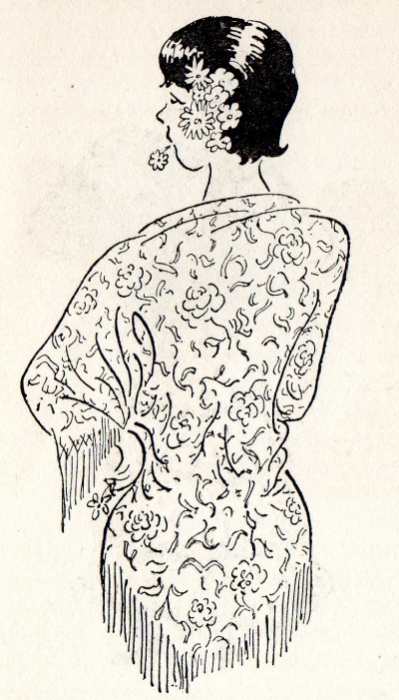

If the ladies of Seville are not crowned, they are at least wreathed; above their ears, in their black hair the carry a whole nosegay, or at least a rose, a camellia or an oleander-blossom; and across their shoulders and arms they wear a silk shawl, with an embroidery of large roses, heavy tassels and a knot at the bosom; or a mantón de Manilla, which is a silk mantle, shawl or robe, studded with an embroidery of roses and tassels, but it has to be worn with an air. It is flung in a serious of folds across arms and shoulder, then it is drawn together tightly, the hands are placed akimbo, the dainty croup is braced outward, and below, there is the clatter of wooden heels; I tell you, to wear the mantón properly demands great skill as a dancer.

What struck me was that Spanish women have contrived to preserve two great feminine privileges; servitude and homage. The Spanish woman is guarded like a treasure, after curfew you will not meet a girl in the streets, and I have even seen street-walkers accompanied by their dueñas, evidently to protect their honour.

I have heard that every male member of a family, from the remotest great-uncle down to the grandson, has the right and the duty to watch, with sword in hand, so to speak, over the maidenly honour of his sisters, female cousins and other relatives.

No doubt there is just a little of the spirit of the harem in this; but at the same time it shows a great respect for the particular dignity of woman.

While man prides himself on his worth as a cavalier and protector, to woman is vouchsafed the renown and prestige of a guarded treasure; whereby both sides, as far as honour is concerned, get their fair share.

But, really, what pleasant folk they are: youths in Andalusian broad-brimmed hats, ladies in mantillas, girls with a nosegay behind their ears and dark optics beneath dropping eyelids; it is good to see how light-footedly they bear themselves, with the strutting gait of pigeons, how they flirt, and with passion and seemliness their eternal wooings are fraught!

And life itself here is sonorous, yet without uproar; in the whole of Spain I did not hear a single quarrel or a cross word, possibly because a quarrel would mean the use of a knife; don’t take it amiss if I refrain from telling you which of these two methods show a higher sense of decorum.