Chapter Twelve - Calles Sevillanas

Calles Sevillanas

I WAGER a bottle of aljarafe, or anything you like, that every guide, every journalist, and even every young lady tourist, will refer to ‘smiling’ Seville.

Certain stock phrases and epithets possess the ghastly and irritating quality of being right.

You can knock me down or call me a purveyor of tushery or an arrant babbler for saying so, but ‘smiling’ Seville really is smiling Seville. Nothing can be done about it; in fact, there is no other way of describing the place. It is just ‘smiling’ Seville; in every corner of its eyes and mouth there is a flutter or merriment and tenderness.

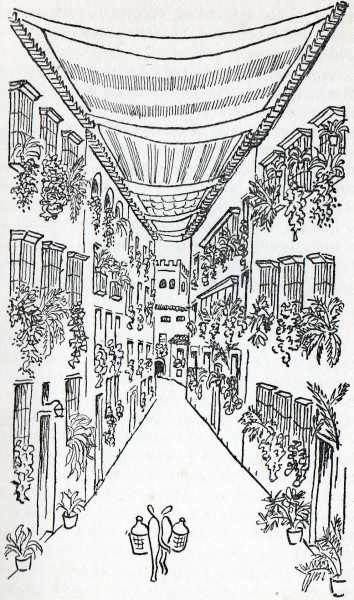

And perhaps it is only that a street, however narrow, glistens as if was freshly whitewashed every Saturday. And that from every window, from every lattice in it are thrust garlands, pelargoniums and fuchsias, small palms and all kinds of greenery, blossoming and leafy.

Here the awnings have still remained for the summer, stretched from roof to roof, and intersected by the sky, as by a blue knife; and when you stroll along, you seem to be, not in the street, but in the flower-laden passage of a house where you are paying a visit; at this corner somebody may perhaps shake you by the hand and say: ‘We are pleased to see you’ or ‘¿Qué tal?’ or something cheerful of that sort.

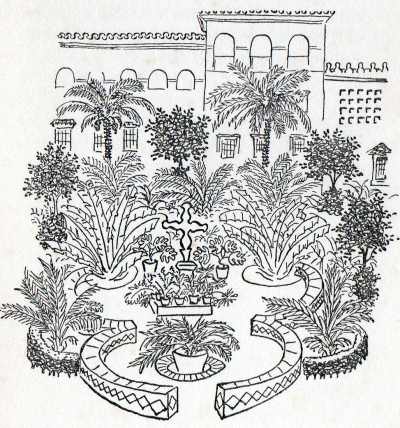

And everything here is as clean as a new pin; there is a smell of garlands and frying oil; every door with its lattice leads to a trim heavenly garden which is called a patio, and here again is a church with a majolica dome and a portal as ornate as if a great festival were on, and above all this the gleaming minaret of the Giralda is uplifted.

And this narrow street is called Sierpes because it twists like a snake; here the live of Seville flows along densely and slowly: casinos and taverns, shops full of lace and flowered silk, caballeros in light Andalusian sombreros, tiny streets where vehicles cannot de driven, because of the crowds of people drinking wine, chatting, haggling, laughing and generally idling there in various ways.

Then there is the old cathedral embedded in the old quarter among the houses and patios, so that you can only see bits of it wherever you are, as if it were too big to be viewed as a whole by mortal eye.

And then another small faience church, miniature palaces which bright and graceful frontages, arcades and balconies and embossed lattices, a notched wall, from behind which palms and broad-leaved musas lean over; always something attractive, a snug corner where you feel at ease and which you never want to forget. Just recall that wooden cross on the little square, as white and restful as a nun’s cell; those delightful, quiet quarters of the city which contain the narrowest streets and the most charming nooks in the world -----

Yes, it was there, twilight had fallen, and the children in the street were dancing the sevillana to the strains of an angelic barrel-organ; somewhere thereabouts is Murillo's house - ye gods, if I lived there, everything I wrote would be tender and cheerful; and there too, is the most beautiful spot in the world; it is called Plaza de Doña Elvira or Plaza de Santa Cruz - no, these are two spots, and now I don't know which one is the more beautiful, nor am I ashamed yet I was moved to tears by their beauty and my weariness.

Yellow and red frontages and a neat garden in the middle: a garden containing specimens of faience, box-trees, children and oleander, an embossed crucifix and the evening peal of bells; and I, unworthy mortal in the midst of it all, murmuring to myself in dazed accents: Good Lord, why, this is like a dream of a fairy tale!

And then there is nothing more to be said, and all that you can do is to surrender yourself to the dazzling loveliness. Of course, you too ought to be young and handsome; you ought to have a magnificent voice and be madly in love with a beautiful maiden in a mantilla, and that will do.

Beauty is sufficient unto itself. But there are various kinds of beauty; among them the Sevillian comeliness is particularly voluptuous and winsome, cosy and affectionate; it has feminine lushness with a crucifix on its bosom, it is fragrant with myrtle and tobacco, and takes its ease in seemly and sensual comfort. You seem to be, not in streets and squares, but in the passages and patios of a house where contented people dwell; you walk along almost on tip-toe, but nobody asks you: what are you doing here, caballero indiscreto?

(There is also a large, brown, diapered Baroque palace; at first I thought it was a royal castle, but it turned out to be a government tobacco factory, the very one in which Carmen rolled cigarettes. A large number of these Carmen's are still employed there, wearing an oleander blossom behind their ears and living at Triana, while Don José has become a gendarme in a three-cornered hat; and Spanish cigarettes are still appallingly strong and black, no doubt through the influence of those dark girls from Triana.)