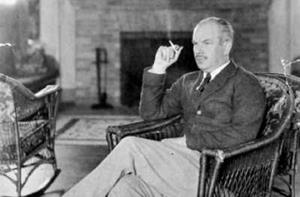

Dr. Norman Bethune

A hero in China, and remembered by the Red Cross in Málaga, this Canadian Physician was born on March 3 1890

There’s a building in Almayate, in the Axarquía district of Málaga province. It is a Cruz Roja specialist training centre, and it is dedicated to the memory of a Canadian physician who was born in Gravenhurst, Ontario on 3rd March 1890.

Norman Bethune - photo www.thegalleryofheroes.com

Norman Bethune was the grandson of a noted physician, and studied medicine at the University of Toronto, interrupting his medical studies to enlist as a stretcher bearer in the First World War.

He specialised in the treatment of tuberculosis after being taken ill with the disease himself – and recovering after innovative surgery – and became a gifted thoracic surgeon. He invented a number of medical instruments, some of which are still in use today.

He turned his attention to the social aspects of medicine, and was an early proponent of universal health care. He opened a free clinic for those who were unable to afford medical treatment, and travelled to the Soviet Union in 1935 to observe the system in operation there. He joined the Communist Party at the end of that year.

Norman Bethune came to Spain in November 1936, along with many other Canadians who fought on the side of the Republican government in the Civil War. At the head of the Canadian medical team, he soon realised that many of the wounded were dying from blood loss before they could reach hospital. He created the world’s first mobile blood transfusion service, performing hundreds of transfusions at the front, and saving hundreds of lives.

On 7th February 1937, Málaga fell to Nationalist forces, and thousands of malagueños fled the city along the coast road to the East, walking the long route to Almería, more than two hundred kilometres away . Seven decades later, the people of the three provinces they crossed to try and reach safety hold a tribute march every February, covering some of the steps the refugees took in February 1937. With them, are some of those who survived. There is also a memorial park in Torre del Mar, which opened in February 2007, in memory of the victims on the Almería road.

They were bombarded from the sea and the air as they tried to make their escape, on what is known as the ‘Caravana de la Muerte,’ ‘The March of Death.’ This exodus of people, the ‘desbandá,’ were in the main civilians, women and children, and the old. Norman Bethune and his team came upon this avalanche of people as they were travelling to the Málaga front to help the wounded, and decided they could not ignore their plight. They spent three days transporting those who were unable to carry on with the journey on foot.

Bethune wrote of it himself in his ‘The Crime on the Road: Málaga-Almeria,’ which includes 26 photographs taken by his assistant, Hazen Sise. He speaks of the pitiful sight of thousands of children, many of them barefoot and their feet swollen to twice their size, and some clad only in a single garment. ‘Two hundred kilometres of misery.’

‘How could we choose between taking a child dying of dysentery or a mother silently watching us with great sunken eyes, carrying against her open breast her child born on the road two days ago.?’ He tells how many of the old simply gave up and lay down at the side of the road, waiting for death.

Dr Bethune worked with Hazen Sise and Thomas Worsley day and night for the next three days, carrying between 30 and 40 people on each trip to hospital in Almería. They initially took only children and mothers. ‘Then the separation between father and child, husband and wife, became too cruel to bear.’ They carried families with the greatest number of children, and children who were travelling alone without any parents - there were hundreds, he said.

He specialised in the treatment of tuberculosis after being taken ill with the disease himself – and recovering after innovative surgery – and became a gifted thoracic surgeon. He invented a number of medical instruments, some of which are still in use today.

He turned his attention to the social aspects of medicine, and was an early proponent of universal health care. He opened a free clinic for those who were unable to afford medical treatment, and travelled to the Soviet Union in 1935 to observe the system in operation there. He joined the Communist Party at the end of that year.

Norman Bethune came to Spain in November 1936, along with many other Canadians who fought on the side of the Republican government in the Civil War. At the head of the Canadian medical team, he soon realised that many of the wounded were dying from blood loss before they could reach hospital. He created the world’s first mobile blood transfusion service, performing hundreds of transfusions at the front, and saving hundreds of lives.

On 7th February 1937, Málaga fell to Nationalist forces, and thousands of malagueños fled the city along the coast road to the East, walking the long route to Almería, more than two hundred kilometres away . Seven decades later, the people of the three provinces they crossed to try and reach safety hold a tribute march every February, covering some of the steps the refugees took in February 1937. With them, are some of those who survived. There is also a memorial park in Torre del Mar, which opened in February 2007, in memory of the victims on the Almería road.

They were bombarded from the sea and the air as they tried to make their escape, on what is known as the ‘Caravana de la Muerte,’ ‘The March of Death.’ This exodus of people, the ‘desbandá,’ were in the main civilians, women and children, and the old. Norman Bethune and his team came upon this avalanche of people as they were travelling to the Málaga front to help the wounded, and decided they could not ignore their plight. They spent three days transporting those who were unable to carry on with the journey on foot.

Bethune wrote of it himself in his ‘The Crime on the Road: Málaga-Almeria,’ which includes 26 photographs taken by his assistant, Hazen Sise. He speaks of the pitiful sight of thousands of children, many of them barefoot and their feet swollen to twice their size, and some clad only in a single garment. ‘Two hundred kilometres of misery.’

‘How could we choose between taking a child dying of dysentery or a mother silently watching us with great sunken eyes, carrying against her open breast her child born on the road two days ago.?’ He tells how many of the old simply gave up and lay down at the side of the road, waiting for death.

Dr Bethune worked with Hazen Sise and Thomas Worsley day and night for the next three days, carrying between 30 and 40 people on each trip to hospital in Almería. They initially took only children and mothers. ‘Then the separation between father and child, husband and wife, became too cruel to bear.’ They carried families with the greatest number of children, and children who were travelling alone without any parents - there were hundreds, he said.

Archive photo

Fifty of the refugees who reached what they thought was safety in Almería died when the city was bombarded by German and Italian planes. Another 50 were wounded. Bethune said the planes made no attempt to hit the barracks or a government battleship in the port, but targeted the city centre where thousands of refugees were sleeping on the main street.

He later wrote that ‘Spain is a scar on my heart.’

Norman Bethune was in China working as a field surgeon for the Red Army’s medical service in the war against the Japanese when he contracted blood poisoning after performing an operation without gloves. He died on 12th November 1939, and Mao Tse-tung wrote in December that year of ‘Comrade Bethune’s spirit, his utter devotion to others without any thought of self,’ in his article ‘In Memory of Norman Bethune.’

Today, he is considered a national hero in China, and is remembered in Málaga province with the Red Cross centre which bears his name, and in Málaga City, with the Paseo de los Canadienses on the beach in Peñon del Cuervo, ‘in memory of the aid provided by the Canadian people, from the hands of Norman Bethune, to the fugitives in February 1937.’ An olive tree and a maple tree were planted at the site, as symbols of Spain and Canada.

He later wrote that ‘Spain is a scar on my heart.’

Norman Bethune was in China working as a field surgeon for the Red Army’s medical service in the war against the Japanese when he contracted blood poisoning after performing an operation without gloves. He died on 12th November 1939, and Mao Tse-tung wrote in December that year of ‘Comrade Bethune’s spirit, his utter devotion to others without any thought of self,’ in his article ‘In Memory of Norman Bethune.’

Today, he is considered a national hero in China, and is remembered in Málaga province with the Red Cross centre which bears his name, and in Málaga City, with the Paseo de los Canadienses on the beach in Peñon del Cuervo, ‘in memory of the aid provided by the Canadian people, from the hands of Norman Bethune, to the fugitives in February 1937.’ An olive tree and a maple tree were planted at the site, as symbols of Spain and Canada.