The unedited diary of a British soldier who besieged Badajoz in 1811

Dating from the time of the War for Independence – the text has been missing for over 200 years

‘Cracked & Spineless’ is the name of a small bookstore of second hand books in the city of Hobart, Tasmania. The antipodes are sufficiently remote to have been able to protect a luxury on one of the most violent sequences defined in history. In Hobart Napoleon’s cannons were never heard, neither the alarms announcing imminent bombing be it from Germany, Japan or the United States. Of course Tasmania has suffered over the passage of time, but the island has had the delicacy to remain isolated from any war.

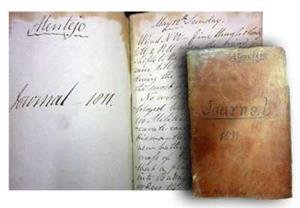

Photo of valuable diary - Cracked & Spineless

History, however, is always found in the manner of remembering memory, even in the antipodes. In this case, in the form of a book, an antique diary which for decades had been buried under a mountain of volumes found inside ‘Cracked and Spineless’. Under a sombre title of ‘1811, Diary, beyond’, the lieutenant coronal John Squire has immortalised his memories of what would be the last campaign: the third assault on Badajoz.

John Squire is not an unknown, far from it. His recently discovered diary is only a grain of sand in the ocean of notes, papers, and volumes which the British soldier left testament for posterity. Squire was mentioned in several military reports, and received honours from several superiors, including honorific mentions by people as relevant as the very Duke of Wellington.

The true value of his figure is, without doubt, the fact that his life was a reflection of the turbulences introduced into a Europe full of modernity. Son of a famous doctor he was born in London, and fought in Spain, Scandinavia, Holland, Egypt and Latin America, he travelled through Greece and the Mediterranean.

Spy, soldier, a lover of archaeology, Squire represented the ideal of the uniformed male engineer who prospered in the twilight of the Century of the Light.

Squire was born in London in 1780, son of an illustrated and reformist doctor. His father founded in 1788 the Society for the Rescue of Widows and Orphans by the Men of Medicine’ a charitable institution which still exists today. Squire belonged to the first generation of professional soldiers, using scientific systems in the exercise of his duty, and graduated in the Royal Academy for Engineers in Woolwich in 1797.

At that time, Europe was involved in a conflict of proportions almost never heard of by the standards of the time. The French revolution has managed to defend itself against the First Coalition, boasting as the main military power on the continent, by occupying the Austrian Netherlands and Holland, where the Batavian Republic was constituted, a puppet state ally of the French.

The proximity of such a formidable enemy and those idealistic Jacobins revolutionaries were a source of perpetual suspicion and unquiet in Great Britain. With the outbreak of the War of the Second Coalition between France, Austria and Russia, the United Kingdom decided to organise an invasion on the Batavian Republic with the aim of opening a second front and to sink or capture the Dutch ships.

Squire had the occasion to participate in the battles of Bergen and Alkmaar. During the campaign, the British managed to neutralise the enemy fleet, although their intention was to defeat the republic and to re-establish the Principality of Orange resulted in a fiasco.

The omnipresent character of Squire is evident when referring to the East, this European centralist concept in the most ancient western cosmogony. In fact, there was hardly any important event on the Ottoman front in which Squire appears in one moment of another.

After the defeat in Holland, Squire embarked for Egypt in 1801 in an expedition commanded by the General Ralph Abercromby with the objective of blocking the successes of Napoleon which he had conquered only a few years before. The importance of this campaign is in capital letters. The very Edward Said, the grand enemy of the eastern Orientalises, signalled the Napoleonic incursions in Egypt as the origin of modern Orientalises.

The direct contact between the European and Muslim worlds was of great importance, and Squire wouldn’t miss it. The curious man he was and a great lover of history, he was present at the French surrender at Rosetta, and formed part of a group of officials who received the named stone from the defeated French. The capture of the Rosetta Stone was a great success: shortly after the British sent the stone to the British Museum (where it remains today). Its study, which is known, allowed the men of European languages to translate the Egyptian hieroglyphs, leading to the birth of modern Egyptology.

He was also in the country of the pharaohs; Squire participated in the battle of Alexandria, a massacre which left more than four million French bodies on African land and which buried the always western dream of Napoleon.

After his services in the African campaign, he started on a tour of the Ottoman Empire in the occasional company of William Richard Hamilton (who wrote on of the first theses on Egyptology, AEgyptica) and William Martin Leake. Together with the latter, Squire found himself involved in the transportation of the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon, acquired in a dubious way by the British ambassador in Istanbul, Lord Elgin, an event, the legality of which has never been proved.

During the voyage, his ship ‘Mentor’ sank near the Kythira Greek Island, which lies opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula, with the loss of some of the sculptures. The wreck, loaded with other antiquities, was discovered in 2009.

As the military engineer he was, Squire was specialised in fortifications and sieges. After his return to England in 1803, the soldier was posted to a series of minor posts, until in 1806 he embarked again, this time destination was Río de la Plata, forming part of an expedition led by Sir Samuel Auchmuty. The objective of the fleet was to capture the populations of Buenos Aires and Montevideo, with the intention to half the flow of silver from Bolivia and Peru.

Squire distinguished himself in the assault on Montevideo, as official in charge of operations: the British managed the breakthrough the fortifications of the city allowing the infantry to take the population by assault. The rising star of the British, however, was exhausted in Buenos Aires, where they suffered a sound defeat at the hands of Santiago de Liniers.

His defeat in Latin America brought him back to Europe, where he participated in a series of actions in Coruña, Holland and Scandinavia until his last destination was confirmed by the orders of the Duke of Wellington in Spain. In campaigns on the peninsular he took part in events, such as the Battle of Torres Vedras and the British advance over Extremadura.

Squire constructed bridges over the Guardiana River which allowed the taking of Olivenza and he entered into combat with the British victory at Arroyomolinos. During the third assault on Badajoz, Squire was working as an engineer for nearly 24 hours without rest. The assault was one of the successes of the British incursion in Spain, the assault on the city converted into a massacre to such an extent the Duke of Wellington is reported to have cried. According to some estimation, the allies left dead or wounded nearly five million.

The very Squire did not escape injury from such a heroic military effort: the man who had travelled from Egypt to Argentina, who had served as a spy and soldier, who was present in the capture of the Rosetta Stone, the movement of the Elgin marbles, succumbed when marching to his next destination. Fruit of a fever he contracted in Extremadura, and exhausted by a rhythm of life which left no time for rest, Squire died on May 19 1812, after just being awarded for his role In Badajoz and honorary mentions by the part of Wellington.

Such is the man who had so many talents now discovered in remote Tasmania the echoes of the awakening of the modern age. Chance had wanted his last diary to be found in Cracked & Spineless, ironically, to close the circle of writings of a personal odyssey. Even if, these historical military campaigns have been well documented, there is no doubt that this last testimony of a singular man, son and protagonist of his own epoch.